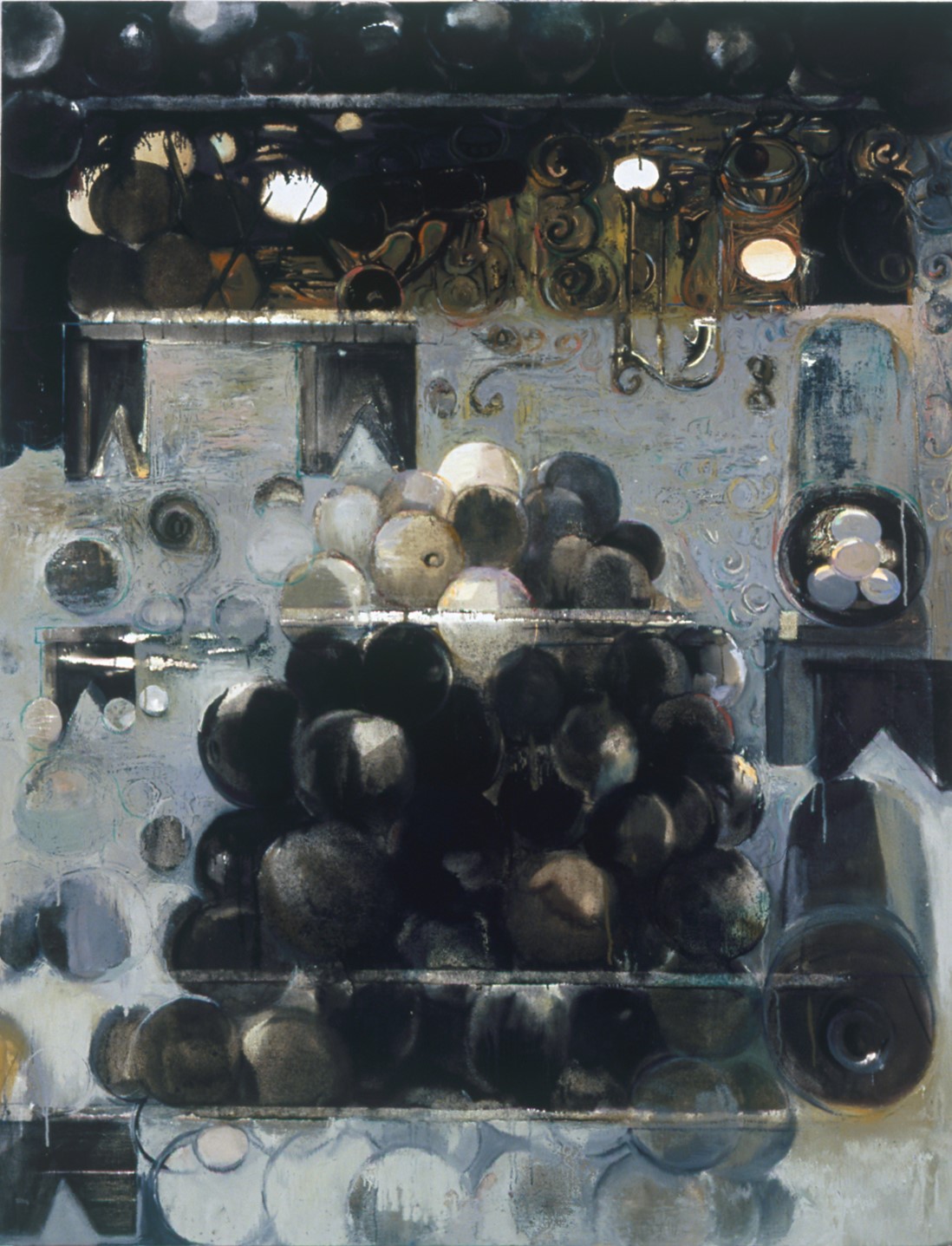

“McFarlane assembles several types of artifacts that associate themselves metaphorically with spiritual concerns. A stool becomes simultaneously a personal icon and a national symbol. The stool, also accurately described as a bench, reminded McFarlane of ones used by artisans when he was just a boy in ‘Old Jamaica’. It stood in for a sense of place and time in his growing up, while also representing creative force–the power to make things as craftsmen did. In the Ghanaian context, the stool embodied the very soul of the nation, the idea of kingship that unites Akan people and finds expression in the person of the Asantehene. Singularly or in clusters, many containers fill much of the remaining picture area. These bowls and jars symbolize the sacred power of water to cleanse, restore, and refresh. The bowls are also an African equivalent of the chalice, for they are also used to pour libations and for communal drinking of wine. Some of the calabash containers offer large hollowed-out interiors that suggest places of protection, places like the womb that both shelter and nurture. Near the bottom left of the picture beneath more containers are a slice of watermelon and the hint of a serpent moving across the floor. Many burning candles, their yellow flickering illumination relieving the dominant brown palette, provide sacred light tying the painting together and uniting the stool with the distant lights of the upper left corner.”

– Barry Gaither Director of the Museum of the National Center of African Artists, Boston

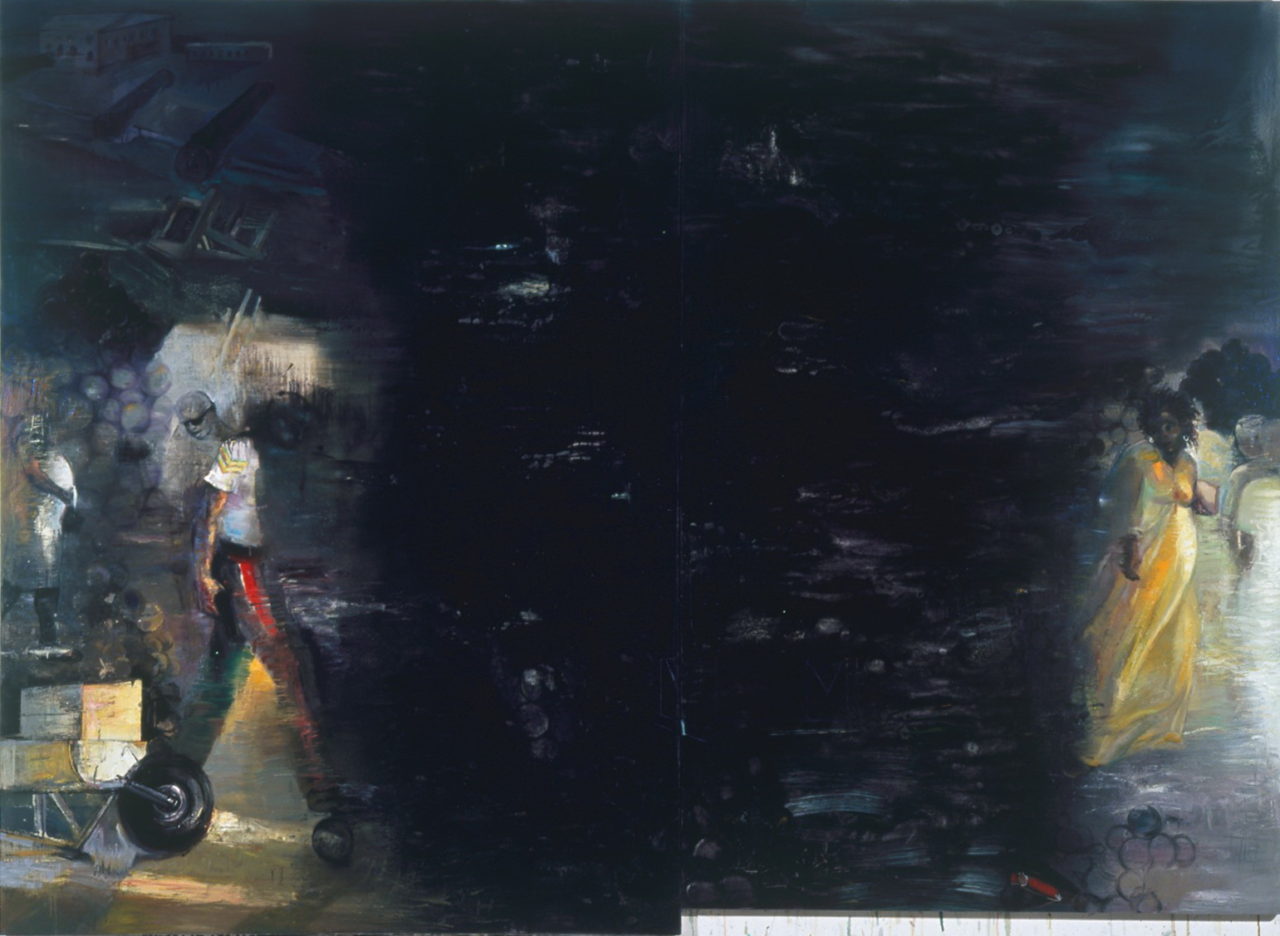

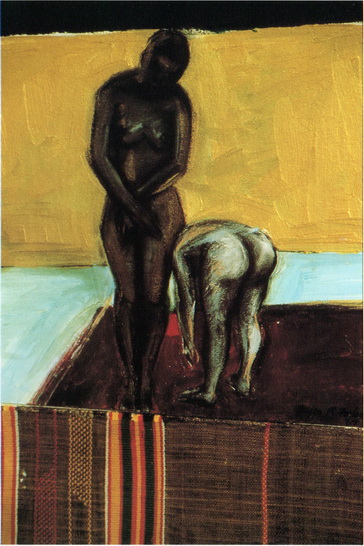

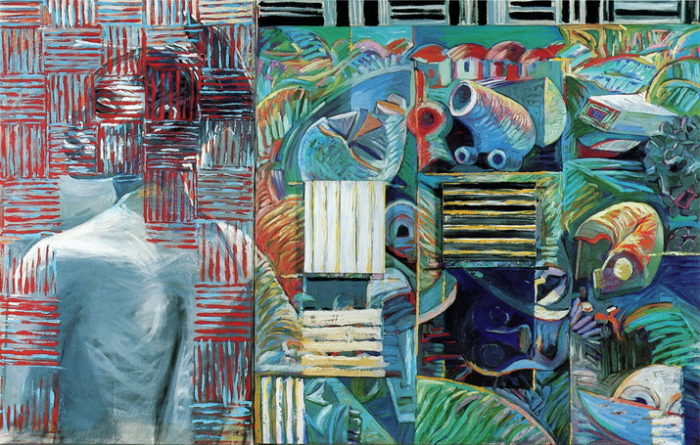

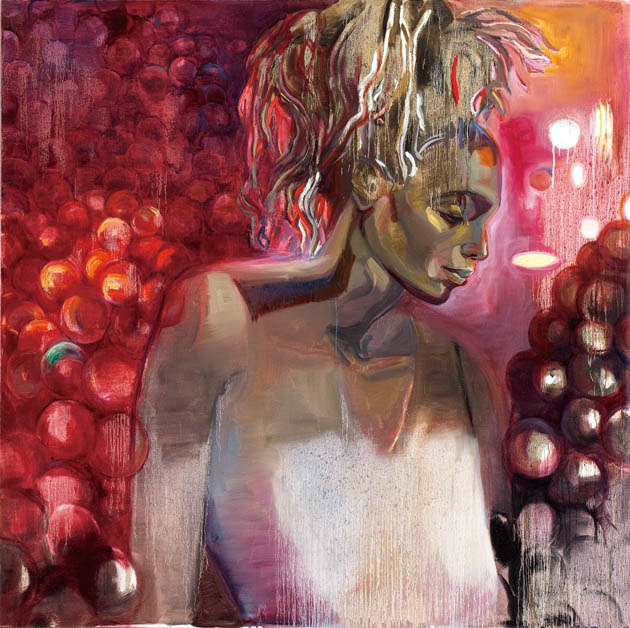

“Ritual Object V from the Ghana Series, 1999, harks back to works inspired by the power of spiritual spaces infused with light that burns through the darkness. McFarlane has responded strongly to such spaces while traveling in Brazil, Ghana and Turkey and sought to evoke the mystery of such sacred spaces with light streaming through stained glass or flickering from candles dispelling darkness. Ritual Objects V offers a foil against which to view his art of the last few decades which explores new directions such as the reciprocal flow of ideas and cultures of the East and West, as well as post-colonial reverberation throughout the proverbial “third world”. Amid these grander themes also appears a new family subjects that simultaneously provide a figurative flashback and a pronouncement of hope and love within a personal context. Fragments of Time II dares to integrate these powerful themes through vehicles of deconstruction and abstraction in ways that create an insightful and fresh perspective within an intriguing and fresh iconography.”

– Barry Gaither Director of the Museum of the National Center of African Artists, Boston